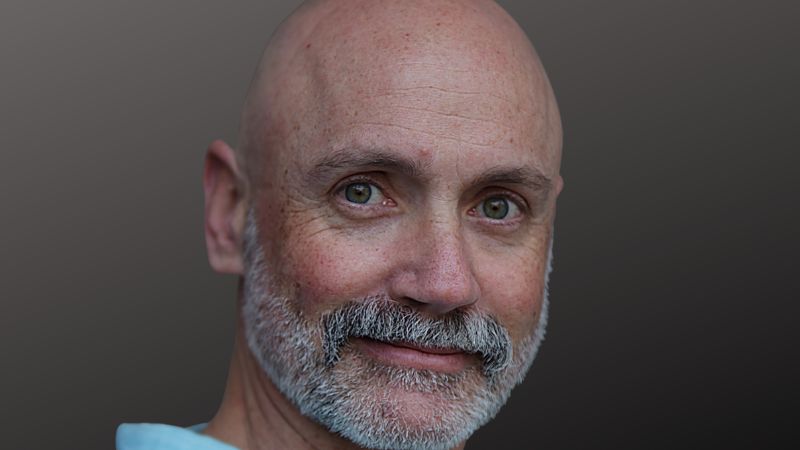

In the world of creative writing, there’s a myth that greatness is born from meticulous, page-by-page perfection. We imagine the writer at their desk, polishing every line of dialogue until it gleams before moving on to the next. But for David Stein, an award-winning screenwriter and Quality Assurance Officer at AFDA, the reality of success is often far more “organic.”

During a recent interview with Spling, Stein confessed to a creative “sin” that every writing manual warns against: he submitted a first draft – the infamous “vomit draft” – to a national competition. That script, ‘Words Like Weeds’, didn’t just get by; it won for Best Unproduced Short Film at the WGSA Muse Awards.

His experience offers a masterclass in why “getting it down” is more important than “getting it right.”

The Trap of the Polished Page

Many writers never finish their scripts because they are too busy trying to make the first ten pages perfect. This “perfectionism” acts as a sophisticated form of procrastination. By obsessing over the universal appeal of a story, writers often strip away the very grit that makes it interesting.

Stein experienced this while attempting to turn a failed novel into a short film script. He found himself wrestling with the fear of irrelevance – wondering if anyone would care about a “middle-aged white man’s fascination with himself.”

“I guess I had a bit of guilt in the beginning, because I’ve been telling students the opposite… Your story might be interesting to you. But it doesn’t mean it’s necessarily relevant just because it’s yours and just because it’s true. I can’t expect an audience to connect with a story just because it happened to me.”

However, by leaning into the raw, personal nature of the draft rather than over-polishing it to fit a “universal” mold, he hit on something authentic.

The 80/20 Rule of Creativity

The interview highlights a productivity principle often used in business but rarely in art: the 80/20 Rule. As the interviewer, Spling, noted during the chat:

“You take 20 percent of the time to get your work to 80 percent. And then to get the extra 20 percent, you have to do 80 percent more work.”

Stein’s win with ‘Words Like Weeds’ suggests that the “80 percent” mark – the version where the heart, flow, and authenticity of the story are alive, even if the formatting or voiceover is heavy – is often what captures a judge’s or producer’s imagination.

The “vomit draft” is the 80%. It is the raw material. If you spend all your time trying to reach 100% perfection, you may lose the momentum required to finish the project at all.

Deadlines: The Great Purifier

Stein’s success wasn’t just about talent; it was about a deadline. He admitted that he “chased a deadline just for the purpose of a deadline,” something he usually warns his students against. But without that hard cutoff, the “not very good novel” might have sat in a drawer forever.

“I got to the deadline and I had one draft and I thought, well, I submit this or I don’t submit anything at all… It didn’t feel much like a process. I just kind of pulled together what I had and then it felt like there was something there.”

The vomit draft forces you to choose: Done is better than perfect.

Authentic Specificity vs. Universal Blandness

One of the greatest dangers of redrafting is “overworking” the script. When we redraft ten, twelve or twenty times, we often try to make the story more “universal” so it can touch everyone. Stein argues that this is actually a mistake.

“The stories that have really done well in terms of touching people, generally-speaking, are the ones that feel very specific and very authentic. Maybe there’s some universal truth in it somewhere, but that’s that specificity, that authentic nature is quite important, too.”

The vomit draft is where your most specific, “too personal” ideas live. In the case of ‘Words Like Weeds’, it was the specific, ritualistic details – a 45-year-old man in a ballet class, the exact texture of a beard trim, the conversation with a 90-year-old rabbi about tattoos – that resonated.

Conclusion: Letting Go

The final lesson from Stein’s win is that a script is never truly finished; it is simply abandoned at the right moment. Whether you are an auteur like David Lynch or a student filmmaker, the goal of the screenplay is to be a blueprint, not a finished piece of literature.

“I’m not sure there are many examples where this doesn’t happen because they connect with it, they love it, they sign on with it. And then it’s like, OK, so here’s what we need to do… Your script is never going to stay the same anyway.”

If the script is going to change during production, during shooting, and again in the edit, why kill your creative spirit trying to make the first draft a masterpiece?

The takeaway for writers: Stop polishing the first act. Vomit out the story. Submit the draft. You might just find that your “raw” is exactly what the world is looking for.